Fixing Ohio's Primary Elections: Why an Independent Ballot Is the Common-Sense Solution for Closed Primaries.

What if the system was not rigged to favor just Republican and Democrats and allowed Independents to apply real pressure to Ohio's major Political Parties.

🔧 What's Broken (And Why You Should Care)

Ohio’s current primary system is like a rigged Monopoly game. Two players (Democrats and Republicans) own all the prime real estate, and everyone else is told to “wait in line,” “roll again,” or “come back next year.”

If you’re an independent or third-party voter or candidate — good luck! The system makes you collect more signatures, wait longer, and spend more money, only to be told you still can’t play. Even worse, folks can jump parties like they’re switching teams in gym class, vote for candidates they don’t actually support, and game the system to rig outcomes. That ain’t freedom, folks — that’s chaos wearing a red, white, and blue necktie.

🎯 The Goal: Honest Competition, Real Representation

A healthy republic thrives on political competition. Without it, parties grow lazy, corrupt, and out of touch. This new proposal creates a Hybrid Closed Primary System with an Independent Ballot — giving power back to the people, restoring integrity to the parties, and opening the door for independent voices to finally be heard.

🗳️ The Proposal: A Red, White, and Blue Ballot

Let’s break this down into digestible parts (don’t worry, we’ll explain with examples and a few allegories):

1. An Independent Ballot – Finally!

Ohio would introduce an Independent Primary Ballot (the “White” ballot) alongside the Republican (“Red”) and Democrat (“Blue”) ballots. Independent voters and candidates finally get a lane of their own. In Ohio the overwhelming amount of registered voters are independents (They show no affiliation to any political party)

Think of it like this: You’ve got three checkout lines at the grocery store. Right now, if you don’t belong to one of the first two, you can’t buy anything. The Independent Ballot opens up that third lane, where everyone else can finally get through.

2. Affidavit of Political Affiliation

Voters must sign an affidavit if they want to affiliate with a party. That means no more last-minute switcheroos where Democrats vote in the Republican primary just to sabotage it (and vice versa).

Rush Limbaugh’s “Operation Chaos”? That wouldn’t work under this plan. You want to be a Republican? Great. But you’ll need to be one for real — not just for one day.

An independent primary ballot has all affiliated and non-affiliated candidates present on the ballot and does not affect your personal affiliation with a political party if you ask for an independent ballot during the primary.

Political Parties such as the Democrat and Republican parties decide before the primary whether or not the votes cast on the independent ballot for their candidates count towards winning the Democrat or Republican primary. The winners of the independent ballot are the top two unaffiliated candidates. They move on to the General Election.

3. A Waiting Period to Vote in a Party’s Primary

Political parties, at their discretion, can require voters to be affiliated for a certain amount of time (up to four years) before their vote counts in the party primary. This discourages fake loyalty and rewards people who actually support the party’s platform.

Allegory time: If you just joined the gym yesterday, you probably shouldn’t get to vote on the gym’s board of directors tomorrow. Work out with us for a bit — then we’ll talk.

4. Caucuses and Granular Voter Education

Within each party and the independent pool, voters can also join caucuses — groups that support specific policy goals. Think “Freedom Caucus” for conservatives or “Pro-Life Independents.” This helps voters see not just what party a candidate belongs to, but what they stand for.

Imagine walking into a bookstore with no sections — just a million books thrown on one table. That’s what Ohio’s ballot looks like now. Caucuses help voters make more informed decisions, not wild guesses.

5. Party Control, Voter Freedom

Each party decides if they want to count Independent Ballot votes for their candidates or not. Parties get to preserve their brand. Voters get to choose candidates based on actual ideas, not just colors.

It’s like letting the restaurant owner decide whether to allow customer suggestions on the menu — without forcing them to serve tofu burgers if they don’t want to.

💡 Why This System Works for Everyone

✅ For Republicans:

Helps to Prevent Democrat interference in Republican primaries - and vice versa.

Encourages loyalty and grassroots involvement.

Helps spotlight conservative caucuses (like pro-life, liberty, or fiscal hawks).

✅ For Independents:

Finally gets representation on the ballot. Vote for the best candidate independent of a specific party.

Allows support of individual candidates, not just parties.

Reduces signature burdens and arbitrary delays.

✅ For Democrats (yes, we’re being fair):

Protects the integrity of their own party processes.

Prevents Republican interference in their primaries.

Encourages true base engagement.

✅ For All Ohioans:

Restores trust in elections.

Encourages voter education.

Fosters true competition — which forces ALL candidates to be better.

🚀 A Quick Peek at the Future

Imagine this:

You walk into the polls. You see three options:

Red Ballot (Republican)

White Ballot (Independent)

Blue Ballot (Democrat)You pick the White Ballot. On it, you can vote for Independent candidates, issues, and — affiliated major party candidates.

You feel like your vote actually counts. Because now it does.

Even if the party does not count the votes on the independent ballot to determine their winner - the primary count can impact the General Election in many ways.

THE SPECIFICS

Understanding Primaries: Fewer Cooks in the Kitchen

Primaries = Tryouts: In our current system, primary elections are basically the playoffs before the championship game (the general election). Think of a primary like a cooking competition – too many chefs spoil the soup, so parties hold primaries to narrow the chef lineup. Voters in each party pick their favorite candidate, thinning the field down to one nominee per party for the general election. This avoids a general election ballot longer than a CVS receipt. (Cartoon: Picture a voter buried under a giant ballot with 50 names – yikes!)

In other words, primaries prevent the chaos of too many choices at once. Without them, we’d risk the dreaded “spoiler effect” – when a minor candidate draws just enough votes to mess up the outcome. In fact, political scientists note that elections without a winnowing primary are highly prone to spoiler chaos. (Imagine splitting a pizza with two friends: if one friend invites a third friend last-minute, suddenly no one gets enough pizza – that third friend is the spoiler who leaves everyone hungry.) Primaries help ensure each party sends one strong contender to the big race, so voters aren’t overwhelmed by a cluttered ballot.

Side Note: The primary’s job is to make November simpler. As one explainer puts it, primaries “narrow down the field of candidates to one individual who will represent the party in the general election”. Generally there’s one Democrat vs. one Republican in November – easy peasy. Without primaries, we could have five Democrats, four Republicans, and seven ninjas running all at once. Good luck picking a winner out of that lineup!

Three’s Company – Making Three Parties Work (Without Chaos)

So primaries are like the elimination round – good. But what if we want more than two choices in November? Enter the big idea: a three-party system (or at least making room for a strong third candidate) without the chaos. Usually, adding a third candidate can split votes and create mayhem. This proposal tweaks the rules to let a “third” option emerge while keeping things orderly. It’s like inviting a third friend to join a duet only after making sure they can harmonize, not just crash the party.

The secret sauce? Give voters freedom of affiliation and give parties some strategic control. In plain English, voters aren’t forced into one of two parties – they can be independent if they want – and parties get to protect themselves from hijinks. The new system preserves your right to choose a team (or choose no team) and lets parties ensure only true fans help pick their champion. The result: potentially three credible candidates in the general election (Democrat, Republican, and maybe an independent or minor-party candidate), without the “split-the-vote” insanity. It’s like adding a third flavor to Neapolitan ice cream, but portioning it just right so your bowl doesn’t overflow. 🍨

Pledging Your Allegiance (or Not): Party Affiliation 101

First things first – Ohioans will formally declare their party or non-party status ahead of time. Currently in Ohio, you’re considered a member of a party if you voted in that party’s last primary (and you stay that way until you miss a couple primaries or pick a different party’s ballot). There’s no separate party registration box you check when signing up to vote; your affiliation is based on your actions. In practice, if you want to switch parties on Primary Day, all you do is request the other party’s ballot. A poll worker might challenge you, but challenges are rarer than Bigfoot sightings. Even if challenged, you just sign a form (essentially an affidavit saying “I swear I’m now a [Other Party] member”) and voila – you can vote in the new party’s primary. It’s pretty loosey-goosey.

The new proposal tightens this up. It says you’ve got to register your party choice (or unaffiliated status) in advance – specifically, about 90 days before the primary. In other words, no last-minute party crashing. If you want to play for Team Elephant or Team Donkey in the primary, you need to sign up ahead of time, kind of like an RSVP. Ohio would shift to a closed primary model where only declared party members get to vote on that party’s nominee. And if you’re new or switching sides, you must update your voter registration by the 90-day mark. In fact, the plan “requires a voter who has changed party affiliation to submit that change no later than 90 days before the primary”. Missing the deadline means you’ll be watching that primary from the sidelines (or choosing a neutral ballot – more on that soon).

Think of it like choosing a team jersey well before the big intra-squad scrimmage. If you don’t put on either the blue or red jersey in time, you won’t be playing for either side in the scrimmage. This helps the parties know who’s really on their team when picking their champion, and it helps you by cutting down on accusations of bandwagon jumping. 🏈

Side Note: You can also choose no team at all by registering as unaffiliated. That’s totally okay! It just means you won’t vote in a party’s primary (you can still vote on local issues or nonpartisan races in the primary, if any). Fun fact: Most Ohio voters today are actually unaffiliated – in 2023, out of ~8 million registered voters, about 5.7 million were listed as unaffiliated. So if you’re an independent-minded voter, you’re in good company.

Switching Teams: What If You Change Your Mind?

Now, what if you’re a die-hard Red voter who suddenly has a change of heart and wants to vote Blue this primary (or vice versa)? Under the current system, as we said, you can do that on a whim – just ask for the other ballot and sign the form if challenged. The new system says: Sure, you can still switch teams… but do it properly, and expect a probation period! It’s like transferring schools; you might have to sit out the big game for a bit.

Here’s the deal: Switching party affiliation will reset your “affiliation count.” Essentially, when you switch, you become a brand-new member of your new party. That shiny “I’m a Loyal Party Member” badge you earned from years of voting in the old party’s primaries? Poof, gone. You start from scratch with the new party. This matters because each party has the right to be a little skeptical of newcomers – especially those who just flipped. The proposal lets parties choose not to count votes from new or recently switched members when picking their nominee. In plain terms, if you haven’t been with the party long enough, the party might say, “Thanks for your interest, but we’re not counting your primary vote this time.”

Why on earth would they ignore votes? Two words: “Party raiding.” That’s the mischief where voters from Party A invade Party B’s primary to vote for a weaker candidate, hoping to sabotage B’s chances in November. Sneaky, right? By discounting votes from brand-new turncoats, parties can guard against this. It’s like a club saying “new members can’t vote on club president in their first year.” They want to be sure you’re there sincerely, not just to throw a pie in their face. So if you do switch sides, be aware you might not get to immediately wield full voting power in the new party’s primary – that’s the trade-off for late switching.

(Analogy time: Imagine you’re a lifelong Coke fan who suddenly joins the Pepsi fan club just to vote in their “New Flavor” contest. Pepsi might be like, “Thanks for joining, but we suspect you just want a weird flavor to win, so maybe sit this vote out.”)

Of course, the details might vary by party. One party could be more welcoming (“Come on in, everyone gets to vote!”) while another might be stricter (“Newbies need to wait one cycle”). The key is freedom for parties to decide their own rules on this. It preserves parties’ strategic decision-making: they can open the gates to independents or close ranks, whichever they think helps pick the strongest nominee. And it preserves your freedom as a voter: you can switch affiliation or be independent – just know the consequences. No more sneaking in at the last minute to tip the scales undetected.

Flying Solo: The Independent Ballot Option

Alright, so you don’t want to wear a team jersey at all – you’re proudly unaffiliated, or maybe you’re a third-party supporter. How do you participate in the primary? Enter the Independent Ballot. This is like the “choose your own adventure” ballot for free agents. If you request an independent ballot in the primary, you’ll get to vote on issues and independent or minor-party candidates only, not on the Democratic or Republican primary contests. By doing so, you stay unaffiliated – taking an independent ballot does NOT change your party registration. It’s a way to have your say without signing up for Team Red or Blue. 👍

Now, here’s an interesting twist: those independent ballots list all the candidates (regardless of party) . But crucially, your choice to vote independent means you’re not counted as a Dem or GOP voter. You’re Switzerland – neutral territory. This new system empowers you to vote for an outsider candidate without “betraying” any party loyalty (since you had none to begin with). It preserves your freedom of non-association – you can vote without being labeled.

However, what if an unaffiliated voter writes in or somehow votes for a major party candidate? Under this plan, the parties get to decide whether those independent-ballot votes will count toward their nomination. Think of it like a sports All-Star game: fans from any team can vote for players, but the league might decide only votes from a player’s home fans count for certain awards. In some states already, party leaders have the latitude to let independents vote in their primaries or not . Here, Ohio parties could say, “You know what, if independents really love Candidate X, we’ll consider that,” or “Nope, only our registered members pick our nominee.” It’s up to each party. This flexible rule ensures that parties remain in the driver’s seat of their nominations while unaffiliated voters still get to express preferences.

For example, suppose lots of independents admire a moderate Democrat running in the Democratic primary. The Dem Party could choose to count those independent votes in the final tally to gauge broader appeal. Alternatively, they might ignore them and only count votes from registered Dems to keep the decision “in the family.” Either way, as an unaffiliated voter, you got to cast your vote without signing on any dotted line for party membership. Not too shabby!

Side Note: This concept isn’t as wild as it sounds. Around half a dozen states let parties decide each election whether to invite independents to their primary. Some years a party will say “Everyone is welcome,” other years “Members only, please.” Ohio’s proposal formalizes this idea: you can always vote on an independent ballot, and then the party can choose if those outside votes influence their nominee. It’s like a restaurant saying “We’ll take suggestions from customers, but the chef will decide whether to use them in the recipe.”

Independent All-Stars: How Two Outsiders Can Advance

Now for the fun part: how do we get that potential third candidate onto the November ballot? This is where the independent primary ballot really shines. Under the new system, independent or unaffiliated candidates (basically anyone not running in the Dem or GOP primary) will battle it out on that separate ballot. The top two finishers on the independent ballot have a shot at the general election if they meet a certain threshold of support. It’s a bit like the wildcard in sports playoffs – the best non-major-party players get to advance, provided they showed they’re serious contenders.

The rule is: an independent candidate must earn at least 9% of the vote count that the top major-party candidate got in their primary to qualify for the general. Huh? Okay, let’s break that down. Say in the Republican primary, Candidate Alice (the winner) got 100,000 votes. For an independent candidate to qualify for the general election, they’d need at least 9% of 100,000 – that is 9,000 votes – in the independent primary. Why 9%? Think of it as a viability bar. It’s high enough to ensure the independent has real support, but not impossibly high. It prevents a situation where someone with like 0.5% of the vote clutters the November ballot. Only credible independents get through.

And why tie it to the top affiliated candidate’s vote count? That makes the threshold scale with how big the electorate is. In a year with heavy turnout (lots of primary votes for the big parties), an indie needs more votes to measure up. In a low-turnout year, the bar is a bit lower in absolute numbers. It’s a clever way to balance things.

So, to recap: after the primaries, we will have: the Democratic nominee, the Republican nominee, and possibly one or two independent candidates on the November ballot. The maximum number of candidates in the general would be four (if two independents hit the 9% mark), but likely it will be three in most cases (one indie clears the bar, or maybe none some years). This is why we call it a “three-party system” – because realistically you’d have three big contenders: one from each major party and one strong independent. (If two independents are really popular – hey, it could happen – we’d have four, but that’s a high-class problem.) The goal is to give independents a fighting chance withoutoverwhelming voters with a dozen names.

Analogy: It’s like American Idol – you have the guaranteed finalists from the main groups (say, the best male and best female singer), and then a couple of “Wild Card” finalists who made the cut by impressing the audience enough. They needed a minimum number of votes to show they belong on the big stage. If they didn’t get that, sorry, try again next time.

Side Note: Setting a threshold for advancement isn’t new. For instance, in presidential primaries a candidate usually must get at least 15% to earn delegates in many states. The exact number (9% here) is tailored to ensure viability in this system. It’s all about balance: include strong alternative voices, exclude the fringe no-hopers. Nobody wants a repeat of that time in history class when nineteen candidates ran and the winner got, like, 20% of the vote. This plan says: if you can’t even get 9% of what a main contender got, you’re probably not ready for prime time.

Win Big or Play Extra Innings: General Election and Runoff

Fast forward to November, the general election. Let’s picture it: you might see three names on your ballot for Governor or Senator – one (D), one (R), one (Independent with a caucus, perhaps). Maybe four names at most, as we noted. Now, how do we ensure the winner has broad support? With three (or more) candidates, it’s possible the “winner” only gets, say, 40% of the vote and wins just because the others split the rest. That feels a bit iffy, right? The new system agrees. So it says: if no candidate wins >50% (a true majority) in the general election, we go to a runoff. 🎉

A runoff election is basically a head-to-head rematch between the top two vote-getters from the general election. It’s like overtime in sports or a final bake-off between the two best chefs. The idea is to ensure the eventual winner has support from a majority of voters. Many places use this for non-partisan races; a few states even require majority for governor or senator. As Rock the Vote explains, in races with multiple candidates, it can be hard for anyone to get 50% because votes are split. The runoff solves that: it’s a second election between the top two candidates when no candidate got a majority in the first round. Whoever gets the most votes in the runoff wins, obviously (with only two, one will definitely have >50%).

So, in our example: if one candidate in November actually breaks 50% – awesome, game over, we have a winner outright. But if the vote totals were: say 45% Alice (D), 40% Bob (R), 15% Charlie (Indie), then Alice didn’t hit 50%. Charlie is eliminated, and a runoff is held between Alice and Bob. That runoff ensures the winner has to appeal to Charlie’s voters and beyond. It’s an extra step, but it gives us a winner who more than half the voters can live with.

One could ask, why not just allow someone to win with a mere plurality (the most votes, even if under 50%)? Well, the point of this whole proposal is to avoid the “spoiler” problem and legitimacy problem that can come with three-way races. If we simply let 45% beat 40% and 15%, folks supporting the loser might grumble that the third candidate “spoiled” it. With a runoff, no spoiling – we get a clear majority decision in the end. In the U.S., Georgia is a well-known state that does this for its elections (you might remember recent runoffs there). It’s all about majority rule.

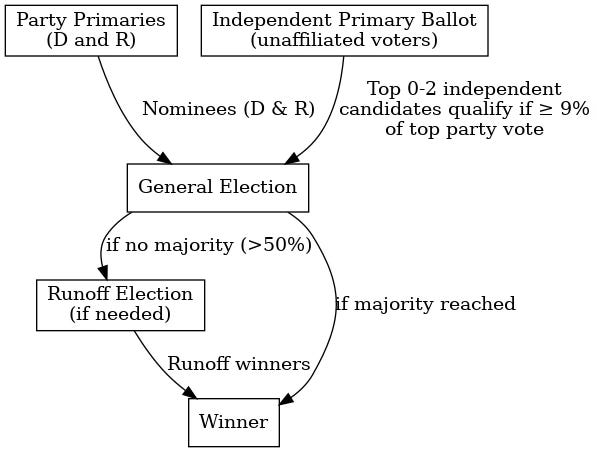

Flowchart: A simplified view of the new election process. Primaries (left: Party primaries, right: Independent ballot) produce the party nominees (D & R) and any qualifying independents (up to 2). They all face off in the General Election. If one candidate gets >50%, they win outright. If not, the top two go to a Runoff Election to ensure a majority winner.

(The flowchart above gives you the bird’s-eye view. Start at the top with the separate primaries, follow the arrows through the general election, and into a runoff if needed. It’s basically Primary -> General -> Runoff (if necessary) – a little more complex than the old system, but not too shabby when drawn out.)

Name Tags for Candidates: Party & Caucus on the Ballot

Now let’s talk about how candidates appear on your ballot. Under this proposal, every candidate’s name on the ballot can show two things: their Party affiliation (or U for Unaffiliated) and their optional “Citizen Caucus” affiliations.Think of this like a name tag with two lines: one for the big party and one for a smaller club or caucus they belong to. For example: John Doe (D)(RTL) might appear, meaning John Doe is a Democrat and a member of the “RTL” (Right To Life) caucus (we’ll explain caucuses in a moment). Jane Smith could be listed as Jane Smith (R)(GREEN), meaning a Republican who affiliates with a GREEN caucus (perhaps an environmental group). If someone is independent with no party, it might say Bob Johnson (U)(GUN) – U for unaffiliated, and maybe GUN for an Independent 2nd Amendment caucus he’s part of.

This dual-tag system is meant to give voters more info at a glance. The party tells you the broad team (Democrat, Republican, or none), and the caucus tag tells you a bit about their specific values or endorsements. It’s kind of like seeing a candidate’s college and their major: e.g. Alice (D) (LBR) might signal she’s a Democrat majoring in labor issues; Bill (R) (RTL) is a Republican focused on Right-to-Life issues, etc. It adds nuance! No more guessing if an independent leans a certain way – they might list a caucus like (LIB) for Libertarian Caucus or (PRG) for Progressive Caucus to give a hint. Even major-party candidates might tout a caucus to differentiate themselves (maybe a (FRM) caucus for rural-minded folks, etc).

Importantly, caucus affiliation is optional – only if the candidate chooses to join one and pay the fee (more on that soon). If a candidate has no caucus, their name might just show one set of parentheses. For example, an unaffiliated candidate with no caucus could appear as “Charlie Brown (U)” (and no second tag). But the format allows for at least two tags and no more than 10 tags, and if used, both will be visible on all ballots – primary and general alike. This consistency prevents confusion.

You might be thinking, “Is listing multiple affiliations on a ballot even done anywhere?” Yes! In New York and a few other states, fusion voting lets candidates appear as the nominee of more than one party – effectively showing multiple affiliations. For instance, the same person might be listed as (Democratic, Working Families) on the ballot. This proposal is a bit different (caucuses aren’t full parties), but the principle of multiple labels is similar. It gives minor parties or interest groups a way to be recognized without running their own separate candidate for every race. Here, those interest groups are called citizen caucuses.

Let’s peek at a sample general election ballot to see how this looks in practice:

Sample Ballot: Each candidate’s name is followed by their party and caucus. In this example, (D) stands for Democrat, (R) for Republican, (U) for Unaffiliated. “RTL” is a fictional Right-to-Life caucus, “GRN” a Green Energy caucus, and “GUN” a2nd Amendment caucus. Voters can easily see both the party and the caucus (if any) that each candidate represents.

As shown above, a ballot might say:

[ ] John Doe (D) (RTL) – meaning John is the Democratic nominee and a member of the RTL caucus.

[ ] Jane Smith (R) (GRN) – Jane is the Republican nominee, member of the GREEN caucus.

[ ] Bob Johnson (U) (GUN) – Bob is unaffiliated with any party (U) and a member of the GUN caucus (a group of 2nd Amendment Supporters).

This way, when you vote, you know not just the party, but also an extra tidbit about what allegiances or philosophies the candidate has signaled via their caucus. It’s like product packaging that says “Organic” or “Gluten-Free” in addition to the brand – more info, better choices!

Side Note: Don’t worry, you won’t need a secret decoder ring for the caucus abbreviations. There will be info about what each approved caucus stands for, in your voter guide or posted at the polling place or on computer election displays. And remember, caucus tags are about issues or ideology, not another full party. Think of it as the candidate’s club membership proudly displayed next to their team jersey.

Join the Club: How to Form a Caucus (and Why)

By now you’re probably curious: what exactly are these citizen caucuses and how do they come to be? You can think of a caucus as an officially recognized political club or faction – not a full-blown party, but a group of folks united by a common interest or ideology who want to be identified on the ballot. It’s a way for like-minded voters to signal support for certain principles across party lines. For example, you could have a “Taxpayers Caucus,” “Environmental Green Caucus,” “Right to Life Caucus,” “Gun Owners Caucus,” “Labor Union Caucus,” you name it. Candidates who align with that caucus’s values can join it and then get that label on the ballot next to their name, effectively telling voters “I’m endorsed by/associated with this group.”

To prevent every John Doe from creating the “John Doe Fan Club Caucus” on a whim, the proposal sets some requirements to form a caucus:

Signatures: You need to gather 5,000 signatures of Ohio voters, and those signatures must be spread out across at least 44 of Ohio’s 88 counties. This geographic requirement ensures your caucus has support from various corners of the state, not just one pocket (44 counties is half the state). It’s a bit of a road trip – you’ll need folks from Cleveland to Cincinnati and everywhere between to sign on.

Filing Fee: You must pony up $5,000 as a fee to the state when registering your caucus. This helps cover admin costs and also weeds out frivolous applications. Think of it as dues for starting your club.

Longevity: Once approved, a caucus is valid for 5 years. It’s not just for one election and done – you get a five-year run before you’d have to renew (likely with another petition or so). That provides stability; voters come to recognize the caucus over multiple election cycles.

One at a Time: This proposal limits candidates to being a member of no more than ten caucus at a time. A candidate can’t list more than 10 caucuses on the ballot – that would defeat the simplicity purpose. So choose the ten that fits best!

Now, say you’ve formed the “Ohio Coffee Lovers Caucus” ☕ (with those 5k signatures because caffeine enthusiasts are everywhere, right?). How do candidates join it? Two steps: money and paperwork. A candidate who wants the Coffee Lovers tag on the ballot must pay a $500 fee (to the Secretary of State for each Caucus listed) and present a notarized form signed by the caucus officers confirming that yes, this candidate is indeed affiliated with our caucus. The notarization just adds a layer of official-ness (no imposters, please). It’s like getting a permission slip signed. Only with that form can the Board of Elections print “(CFE/ Coffee)” next to the candidate’s name.

Why charge candidates $500? To help fund the Secretary of State’s administrative costs. Also, it ensures candidates have some skin in the game. They’ll only list a caucus if they really mean it. From the caucus’s perspective, they might use those funds to help promote their platform or hold conventions.

This setup basically creates mini-parties or interest groups that are transparent to voters. It’s an innovation to amplify voices without breaking the two-party framework entirely. Minor parties that struggle to meet the high bar to become official parties in Ohio (which requires tens of thousands of signatures and a vote threshold) could instead rebrand as caucuses. For example, instead of the Libertarian Party running its own candidate for governor and risking spoiler effect, they might form a Libertarian caucus. Then a Republican, Democratic, or Independent candidate who is Libertarian minded could join the LBT caucus and carry that banner on the ballot. Voters see (R)(LBT) – meaning a Republican endorsed by Libertarians – which might attract Libertarian Party folks to support them without splitting the vote. Neat, huh?

Side Note: By comparison, forming an official new political party in Ohio is much harder: it currently takes signatures equal to 1% of the last gubernatorial vote (that’s on the order of ~50,000 signatures statewide) and your candidate for governor or president must then earn at least 3% of the vote to keep the party status. The caucus route (5,000 signatures, no vote percentage requirement) is a more attainable way to organize politically. It’s like the difference between starting a new restaurant from scratch (party) versus opening a food truck (caucus) – fewer hoops to jump through, but you still get to feed people your unique recipe.

Wrapping Up: The More (Parties) the Merrier?

In summary, this three-party election proposal for Ohio shakes up how we do primaries and general elections in a big way – aiming to welcome new political voices without turning the election into a free-for-all. Here are the key takeaways in plain English (no dummy left behind):

Primaries still happen – they remain crucial for narrowing the field and avoiding choice overload in November. But they’ll be closed or controlled: you must register your party (or lack thereof) ahead of time, and no sneaky party hopping at the last second.

Voter choice is respected: You can be Democrat, Republican, or neither. If neither, you get an independent ballot so your voice is heard even if you’re not team Red/Blue.

Parties get control: They can protect themselves from fake fans (raiders) by disregarding brand-new switchers’ votes, and they can decide if unaffiliated folks’ votes should count toward picking their nominee. They keep the keys to their clubhouse.

An open door for independents: Viable independent or third-party candidates can earn a spot in the general election by proving themselves in the independent primary. Meet the 9% threshold and you’re in the big show, potentially giving voters a third choice in November.

Majority rules in the end: The general election winner needs a majority (>50%). If no one hits that, we have a runoff between the top two – ensuring the ultimate winner has broad support. No more winning with a mere plurality when more than half the voters wanted someone else.

More info on the ballot: Candidates can proudly display both their party and a caucus affiliation. This helps break the one-dimensional D vs R narrative and tells voters more about what a candidate stands for (e.g. a caucus for gun rights, environmentalism, etc.).

Caucuses = political clubs: Citizens can form caucuses relatively easily (5k signatures, $5k fee) to promote issues they care about. Candidates can join a caucus ($500 fee + form) to get that label next to their name. It’s a novel way to organize politically without forming a whole new party bureaucracy.

Will this system make Ohio politics as friendly as a church picnic? Probably not overnight. 😜 But it aims to give voters more choices and more information, while keeping elections fair and functional. It’s like adding an extra lane to a two-lane road – hopefully reducing traffic jams, not causing pile-ups. Voters can affiliate how they want, parties can strategize to win, and strong independent voices aren’t automatically doomed as “spoilers.” In theory, everybody wins! Or at least, everybody gets a shot.

So the next time someone grumbles about “only two choices” or fears a third-party “stealing votes,” you, dear reader, can explain how a three-party friendly system might work. And you can do it with a smile. After all, democracy doesn’t have to be rocket science – sometimes it just takes a little creative re-engineering . Happy voting! 🎉

📣 Final Thoughts: Let Freedom (and Competition) Ring!

Ohio’s election system doesn’t need a tweak. It needs a wrench, a hammer, and a shot of constitutional caffeine. This proposal doesn’t destroy the current system — it simply fixes it so that it serves all voters, not just the chosen few.

If we’re going to talk about freedom, integrity, and fair play, then let’s prove we mean it. Let’s make Ohio a beacon of ballot fairness — red, white, and blue.